Pubished in Key Notes, October 1996

Love, death and the pencil-sharpener

by Frits van der Waa and Emile Wennekes

Working boldly on the grand scale Cornelis de Bondt

strives to recapture the space and depth of tonality. He is

assisted in the task by a battery of computer programmes. But

cerebrality is only one side of the coin. `Watch out, he might

well be the most intuitive of us all!'

Their last recorded sighting was in a glass jar standing in

the room of the Viennese coroner's assistant Anton Dotter.

After that the trail goes cold. A few years after his death,

Beethoven's damaged petrosal bones (from the inner ear)

disappeared, but that is less of a disappointment than the

doctors would have us believe. It is true that modern medical

analysis of these relics might explain the cause of his

deafness, but we would at the same time be deprived of a host

of spicy speculations. Did Beethoven suffer from syphilis? A

bone condition? Or Paget's Disease? Was Hyperostosis

Corticalis Generalisata the cause, or was it Van Buchem-Hadder's Disease?

The explanation can also be sought, however, in a quite

different area: in the music itself. One of the most

intriguing ideas on Beethoven's deafness comes not from a

doctor but from a composer: Cornelis de Bondt (b. 1953 in The

Hague). His theory is that Beethoven could not help but go

deaf because, while composing, he was constantly hearing the

piece upon which he was working in its entirety – indeed, he

must have been, or he would not have been able to write such

organic music. Cornelis de Bondt took this theme as the

subject for his music-theatre piece Beethoven is Doof

[Beethoven is Deaf] (1993), but he also uses the metaphor of

Beethoven's deafness to express an essential problem which

remains a daily experience for the contemporary composer.

De Bondt: 'In the development of the First Movement of the

Fifth Symphony there is a fantastic movement. From g minor he

goes right down and finally comes out in A double flat major.

And then the incredible happens! Just before the reprise he

brings about a inimitable synthesis between the mottoes of the

first and second themes. The rhythm is that of the second

theme motto, the pitch is based on the thirds from the first

theme. At this point the A double flat changes into the key of

G. In a fraction of a second he shoots through the circle of

fifths. You hear the moment of transition because this G

suddenly turns out to be the dominant in C again. Et voilà:

the reprise has begun. For me that moment is the symbol of the

perfect synthesis. That is turning form into object.'

'The consequences of this are awesome, because if you think it

through it means that every time you have an idea you also

have to compose its relationship with all the other moments.

Thus you have constantly to hear the piece as a whole. Then

you go deaf. It can't be otherwise. This is the ultimate

result of the discovery of musical notation. From the moment

that music is written down, the composer is obliged to oversee

the whole, because otherwise he might as well be improvising.'

In order to oversee the whole, to realize order and unity in

his compositions, Cornelis de Bondt makes use of an ingenious

system of computer programmes which is being constantly

perfected as the years go by. You could say that, on the one

hand, De Bondt uses the computer like a medieval model book,

where isolated figures and forms were written down to be later

adapted in endless variations and disguises into new works of

art. On the other hand, the computer functions as a clever

assistant who can rapidly screen innumerable models for their

suitability.

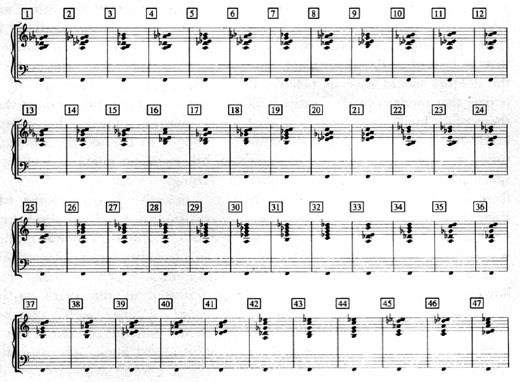

De Bondt: 'For example, I use this chord from De Namen der

Goden [The Names of the Gods] (1992-92), my piece for two

piano's and electronics, as a model [chord 4]. I start by

analyzing the chord to discover why the sound appeals to me.

The bass is nice and low in relation to the other notes, there

is an augmented triad but at the same time it has something

tonal about it; I hear a major sixth, a minor second

inversion. I then give the computer the task of producing

chords in which there must be at least a tenth distance

between the lowest two notes, and I put in a number of other

preferences and limitations. For example, I don't want

conventional root triads to be in there. Suppose I want to use

a series of six note chords as the foundation for a piece,

based on the mode C/C♯/D/E♭/F/F♯/G/A/B♭/C (that is; three

minor seconds, major second, two minor seconds, major second,

minor second, major second). I then encode this series via

numbers in the programme and set the computer computing.

'Out of half a million possible chords the computer takes less

than an hour to select around 50 which are all built on the

same bass note. I then play through all these chords on the

piano and immediately throw a lot of them away. This

consonance [chord 7] is too jazzy – you have to watch out with

diminished chords – chuck it. This chord [chord 9] sounds like

a Hollywood gangster movie – no good. In the end there is only

a handful of usable chords left.'

Thus on this basic level a degree of unity is already

guaranteed. One side effect of this method is that it sets the

composer off on new tracks and becomes a kind of self-generating system

providing almost inexhaustible riches.

The model chosen might be an original chord for De Bondt to

embroider upon (as with this chord from De Namen der Goden) or

it can refer to something else (as if the composer briefly

assumes the role of chorographer attempting to recapitulate

the musical landscape from a distant past in a single

gesture). The placing of a diminished seventh chord in the

piano piece Grand Hotel (1985-89) presents the listener with

the whole spectrum of Beethoven's piano sonatas in freeze-dried form. And not

just the sound, but a whole pianistic

tradition. 'De Bondt sets the world of the piano virtuosi, who

are primarily concerned with phrasing, use of the pedal,

legato and other facets of the sound, against that of

musicians for whom the notes come first', writes Paul

Luttikhuis in the Donemus brochure (1993) on De Bondt.

And just as one little chord can stand as a model, so a

complete composition can function as a matrix, without being

automatically expressed in quotations which are immediately

recognizable as such. The ground plan of Het Gebroken Oor [The

Broken Ear], written in 1983-4 for the Schönberg Ensemble, has

its origin in fragments from Schönberg's Kammersymphonie op.9.

In the orchestral work De Deuren Gesloten [Doors Closed]

(1984) the funeral march from the Eroica is reworked, as is

the aria 'When I am laid in earth' from Purcell's opera Dido and Aeneas. There

are other examples: in La Fine d'una Lunga

Giornata (1987, for large ensemble) the listener hears a

quotation from Stravinsky's Requiem Canticles and use is made

of a chord series taken from the B flat minor fugue from Book

I of the Well Tempered Klavier. Dame Blanche (1995, for large

orchestra and recorders) is founded on four medieval songs,

and we can also hear fragments pared from Fauré's song, La

Lune Blanche.

De Bondt: 'In Het Gebroken Oor I was not particularly

concerned with penetrating to the musical essence of the

Kammersymphonie op.9. The starting point in this case was

purely anecdotal: the complement of the Schönberg Ensemble

happens to derive from the Kammersymphonie. At the same time I

wanted to do something about the destruction of tonality and

this piece was an ideal starting point. But it is decidedly

not a remake of the Kammersymphonie in another idiom. To a

certain extent the source work is exchangeable; the important

thing is that I am doing something with the past, and with the

tonal past in particular. And that is because I think that

tonal music possessed a depth, a dramatic dimension, which in

my opinion has been lost in the twentieth century. I would not

even think of writing more tonal music today, but there is a

problem here which interests me and I want to solve it as a

composer, not as a theorist.'

Working from the overall form is essential for De Bondt and

here too the computer renders invaluable service: 'Given the

enormous quantity of data generated by the computer, I can

choose to adopt a rough method of writing, a kind of crude

brush work, in which you lay down a whole layer in one stroke;

a rapid sequence of chords, for example. That is just one

thing, the actual order is not so important. My real task is

to then set something against it, a line or a single note,

which enters into a dialogue and thereby becomes suddenly very

important. This is way of creating a feeling of space and

depth again. For me, it creates a more interesting kind of

complexity than in, say, Ferneyhough, who is not concerned

about a hierarchy, but merely with adding all sorts of

complicated layers. I find it more interesting and actually

more complicated for there to be less, but with meaning. That

is the advantage of using pieces or fragments from the past.

These things sit in your memory, every listener knows them. If

you hear a second inversion, you immediately hear all those

other pieces. Then you have meaning, and when you add

something else to that you create tension.'

This re-use of tonal works from the past provides what De

Bondt calls a 'borrowed' sense of drama. 'In one way it is a

bit dishonest, a bit like stealing. But if it produces a nice

piece, let's get on with it. In fact, I have only done it

directly in a limited number of pieces. And in the end the

threshold turns out not to be so solid. In pieces like Dipl'

Ereoo and De Tragische Handeling [Actus Tragicus] I just made

my own chords, and if I look back now I am struck by the fact

that a similar sort of idiom was produced, even without old

music as a basis.'

By adopting such a model-based, abstract or conceptual

approach, Cornelis de Bondt inevitably gives the impression of

being a cerebral composer. Even at his final exams at the

Royal Conservatory in The Hague somebody was beginning to imply

as much, but De Bondt's teacher, Jan van Vlijmen, put in:

'Watch out, he might well be the most intuitive of us

all!' And that 'us' was aimed at a board of examiners which,

besides Van Vlijmen himself, included Louis Andriessen, Dick

Raaijmakers, Ton de Leeuw, Frederic Rzewski, Jan Boerman and

Theo Loevendie.

All De Bondt's pieces are written with a specific musician or

group of musicians in mind. When he begins a piece the very

first thing he does is to imagine himself sitting in the

audience: 'I ask myself, "What am I hearing?" Not just the

first moment, but what is this piece as a whole doing here?

That is what I call the soul of the piece. For as long as I

have no answer I do not write a note. When I have the overall

form – and that again is a matter of intuition – then it goes

quite quickly. But only after a lot of brooding and cursing

and careful thought.'

According to De Bondt the cerebral aspect is limited to the

tools, to the computer in this case. 'The role of the cerebral

system is comparable to that pencil sharpener over there; it

is a technical aid. You can have a load of nice ideas, but at

a given moment they must be materialized. And for that you

need techniques, and that involves craftsmanship. It is

intuition which makes the piece, which ultimately determines

its identity, which lends the soul to the music. But the one

cannot exist without the other. Both aspects are necessary and

are powerless without each other. That is the interesting

thing about art in general and about music in particular. This

is why I find Bach such a good composer. His music is both

cerebral and intuitive. The musicality of the fugue structures

and contrapuntal principles goes far beyond the intellectual

aspect. He plays with it, he sublimates it. Maybe that is why

Bach puts in an appearance in so many of my pieces.'

*

(a telephone rings)

'Good Evening, Amsterdam Callgirls'

(the buzz of a filling concert hall rises from the left–hand

speaker; the telephonist's voice continues from the right:)

'Yes, we can do that, we have ladies to visit gentlemen

at home or in a hotel....we have a variety of ladies

available; from Holland, the Caribbean, South America and

Asia.'

So runs the intro to Ecce Homo, a radiophonic composition

which De Bondt made for the Dutch broadcasting company NCRV

early this year. No abstract notes here, but several sounds

from the everyday world, where fragments from a performance of

the St. Matthew Passion sound as much like news footage as the

other two ingredients: the sound of a rowing boat and the

panting and sighing of a prostitute at work.

The reality here is unashamedly direct, even voyeuristic. But

here too we find the ordering hand of the composer. The

'client' has been completely cut out, which in itself produces

a strange stylized effect. 'It is a sort of Bach fugue in a

way,' says De Bondt. 'All the coughs and kisses which you hear

in the places between the arias are organised with numbers as

in Bach. The sound man did not know what had hit him. Two

seconds of this, three seconds of that. Terrific.'

For this remarkable project a real callgirl and an actor were

taped up with microphones and wires and went to bed together

for the sake of Art. De Bondt himself, ears plugged with

miniature microphones, recorded a performance of the Matthew

Passion 'The initial idea was even to make it a live

broadcast,' says De Bondt, 'which had to do with the nature of

radio. The commission was to make something about Holland, so

I immediately thought of water: sewers, lock-gates. Those are

nice sounds sure enough, but you still have no music. Then I

thought of the Matthew Passion, which has long been such an

important part of musical life in the Netherlands. But while

you sit on the pew listening to Bach for three or four hours,

someone else is going whoring. I found it an interesting idea

to combine these different worlds.'

With the water providing a sloshing, surging link, De Bondt

succeeds in all but abolishing the boundaries between the

sacred and the profane. The Bach fragments are so selected

that they always have some bearing on the sex scene. Thus the

play reaches a climax in a sort of Bach orgasm, on the words

Sind Blitze, sind Donner in Wolken verschwunden [The

lightning, the thunder have vanished in the clouds]. And we

even have a moral, because after the callgirl's mundane

comment, 'Time's up', the choir comes in with O Mensch, bewein

dein Sünde gross [Oh Man, repent thy great sins].

Similar excursions beyond the domain of the notes, extravagant

for a composer and not always comfortable for the listener,

crop up increasingly in De Bondt's recent work. In another of

this year's pieces, Singing the Faint Farewell, alongside the

aural component – a Thomas Weelkes madrigal played in slow

motion and a web of percussion slowly closing in on itself –

he prescribes a visual obligato counterpoint in the form of a

dancer who slowly undresses herself. Another combination of

the vulgar and the exalted?

'It is not meant as a striptease,' explains De Bondt.'There

must be a hint of the erotic in it, but ultimately it must be

the opposite. Because dying – which is what the madrigal is

about – is not so erotic. It is intended more as a symbol of

nakedness, the idea that you must leave everything behind you

when you die.'

For De Bondt the action was an integral part of the piece from

the outset ('I rang immediately to see if it could be done.

Because otherwise I would have written a whole other piece').

The audience which attended the premiere in the Utrecht

Muziekcentrum found it hard to cope with. But how did the

people who were listening on the radio manage? Did they not

miss something essential? 'Certainly,' admits De Bondt. 'But

that is true for every piece. A symphony orchestra in the hall

is utterly different from one on the radio. It is just the

same in pop music. I do not understand the people who only

listen to CD's. You have to hear music in the hall. That is

theatre too, seeing people play.'

This is overwhelmingly true of De Tragische Handeling,

composed in 1993 for the ensemble LOOS. A live performance of

this piece produces an effect to which not even the most

brilliant recording can do justice. Strangely enough, the

dramatic charge relies to a major extent on the contribution

of the electronics (four digital resonance processors,

operated by the musicians themselves) which stretch the chords

fed in by the players to virtually infinite lengths.

Long notes: here more than in any other of his works, you can

still hear the effect of the shock produced on De Bondt the

student, who was little more than a blank page musically, when

he first encountered the music of the thirteenth century

organum composer Perotinus. In De Tragische Handeling the long

notes stack themselves up into chords like tongues of flame, a

titanic curtain of fire in the middle of which the five

musicians stand to beat, slave and sweat like mythical smiths.

De Bondt's tendency to 'theatralize' has gone so far that a

lecture which he recently gave at the Arnhem Academy of Art

was couched in the form of a performance. 'I come there as a

composer; so the lecture therefore had to be composed, to show

what someone like me does.' The text of the lecture was

interspersed with several blows on a gong and with fragments

from Jorge Luis Borges' The Aleph. Not surprisingly, the idea

of the Aleph, 'the place where all the places of the world

come together, without overflowing into each other, and seen

from every angle', is for De Bondt the perfect metaphor for

the composer's ability to oversee the structure of the still

unwritten work in its entirety.

Just as a lecture can grow into a performance, so a

performance can take the form of a lecture. Beethoven is Doof

[(Beethoven is Deaf], which was performed in 1993 in

Rotterdam's Disco Nighttown, is essentially a textual

composition. Here too De Bondt gets 'old' and 'new' meanings

to bounce off each other. While an actor (Hans Dagelet) reads

Boulez's notorious article Schönberg is Dead, we

simultaneously hear a tape of De Bondt declaiming, in almost

identical words, his own text Beethoven is Doof. He himself,

alive and kicking, sits behind a piano and mimes to a

recording of the largo e mesto from Beethoven's Sonata op.10

no.3, which is gradually compressed by a digital resonance

processor into a diffuse piano pulp.

De Bondt regards such pieces, with spoken text, electronics or

dance, as preparatory studies for a large projected music-theatre work,

to be called De Man van Smarten [The Man of

Sorrows]. 'I really want to do this with a team,' says De

Bondt. 'A group of us have already talked it over a few times,

but it still has a lot of maturing to do.' What he has in mind

is a production where two operas are laid on top of each

other; one layer follows a traditional nineteenth century

model, with characters who are driven by love and jealousy;

the second layer is a 'performance', produced by a small group

of musicians with electronics, which at given moments must

intervene in the underlying drama like a deus ex machina.

The work may still be at the ideas stage, but the ideas are on

the grand scale. 'The Man of Sorrows, that is Jesus,' De Bondt

explains. 'But Jesus himself does not appear; it is actually

about two other stories, those of Pilate and Tacitus. The idea

is taken from the theories of Robert Ambelain, a French priest

or ex-priest. According to him, the authorities in Rome tried

to put Jesus, who was a descendant of Judah after all, on the

throne of Israel to keep the province under control. Herod was

King at the time, and he was naturally against it. Pilate too.

According to Ambelain the authorities were furious that Herod

and Pilate had had Jesus killed and they were banished or

kicked upstairs. That is historical fact: Pilate was later

transferred to Vienne in the French Alps.

'The Tacitus story comes much later. That has to do with the

censorship which Ambelain says took place when Christianity

became the official religion in Rome. All the different

stories and legends had to be reforged into one official

version. It so happens that Tacitus' book describing the

province of Palestine disappeared at the same moment. And

Ambelain says: "This is no coincidence. It contained things

which were not in the interests of the official religion."

What I want to do now is to rewrite this book.'

This account, a story about overlapping stories, contained

within a structure where the theatrical and the abstract

overlap each other in a similar way, is typical of De Bondt's

attitude as a composer; namely, a microscopic approach to the

tiniest details coinciding with the macroscopic effort to roll

up Time into the ball of one eternal moment. It is an attitude

which has characterized his music from the very outset. 'Over

the years I have developed all sorts of techniques and then

built on them', he says, 'but, rather like Mondriaan, I still

have the feeling that I am painting the same tree.'

(transl.: Rob Bland)

© Emile Wennekes / Frits van der Waa 2007