Published in Key Notes, september 1995

'Too short or too long, that's what intrigues me'

The voice of Jan van de Putte is a unique one in Dutch music. His music is as

powerful as it is silent. It is about untruth being the truth, about the point being the

turning-point, about counting as well as what really counts. 'I think that this is my

whole concept of life – that you can't separate things from one another.'

An enormous page with nothing on it except instructions on how to turn to the next one.

A bar's rest, with above it a fermata marked troppo lunga. As paradoxical as it sounds,

Jan van de Putte has a clear predilection for composing with silence. Silence is not his

only tool, though. After all, silence only gains significance from what follows or precedes

it. But even the things Van de Putte highlights with silence are not necessarily audible. To

give an example, in his long composition for solo kettledrum, Om mij mijzelf met mijn

aan mezelf en mezelf en mijn eigen [To me myself with my to myself and myself and my

own], several of the many silences are separated by sharp blows on the kettledrum which,

however, 'rebound' just before hitting the drum-head.

Van de Putte's work often goes far beyond the boundaries of what is normally

considered music. It strays far from the beaten path, tinkering with its own limits and

sometimes even crossing over into the realm of performance. But then, even its theatrical

side has a musical, composed impact.

The creator of this stark and austere music, by contrast, turns out to be a buoyant and voluble

personality. Seated at the kitchen table in his Rotterdam apartment, he gives free rein to his thoughts

and associations.

'For years I composed without even a single work getting performed', he relates. 'It

didn't really matter to me at the time – and, basically, I still feel the same way. In fact, I

even remember feeling a bit of remorse when something finally was performed – that was

In hora mortis, a long composition –, as though it was no longer my piece and I had to say

goodbye to it. I owe it to Klaas that I learned to cope with that kind of thing.'

Klaas de Vries, with whom Van de Putte sought refuge after not entirely successful

studies of musicology, composition and music theory, was initially at a loss for what to

do with his new student. As he related several years ago in a Netherlands Broadcasting

Company radio programme: 'When he first came to me I thought: "Dear God, this is so

far removed from anything I do, what can I possibly say about it?". I finally decided to

concentrate on toning down the extreme edge in his thought and on trimming his music to

performable proportions.'

'Klaas threw me, so to speak, into practical music', says Van de Putte. 'He's the only

one, too, who really taught me anything. Most importantly, to think practically, to keep at

it. Not to get lost in dreams or details.'

De Vries's lessons bore fruit. In hora mortis won Van de Putte third place at the

Rostrum of Composers as well as the Encouragement Prize of the Amsterdam Fund for

the Arts. But despite his greater practical experience today, Van de Putte does not always

seem able to keep a leash on his creative processes. 'My pieces are invariably gigantic

projects', he says. 'They tend to remain incomplete. It used to be I would openly admit it,

and then they wouldn't get performed. Today, I keep that bit of information to myself,

and they do get performed. It's as simple as that.'

All told, there are five compositions in his list of works: Essenz, a string quartet,

written in 1985 ('Actually, I rejected that piece ages ago.'); In hora mortis, for mezzo-soprano and

orchestra ('I don't intend to finish this one any more. Well, maybe when I'm old, if my imagination dries

up.'); Es schweigt, for soprano and ensemble ('That's only the first half of it');

and the previously mentioned kettledrum solo, Om mij mijzelf [ ... ], his sole fully

completed work.

Finished or not, Van de Putte's music does not fail to capture and hold one's attention,

if only for its sheer radicality. Es schweigt doggedly explores a single tone for minutes.

Musical tension is shaped by timbre, register, articulation and timing alone. And the

hysterical outburst near the end – or rather, the provisional end – forms no less imposing a

climax than the half-bare pages where a lonely double bass fires off salvos of col legno

ricochets. At the first performance the bassist played his part with such verve that he

broke his bow in two, which all but destroyed the piece. Proof, perhaps, that Van de

Putte's constructions, as heavy and ponderous as they may seem, are of a tautness that

makes them extremely fragile at the same time.

Van de Putte's main objective is to infuse his music with meaning. In this regard, he

mentions Mahler as one of his great models, though this can hardly be heard in his work.

'The most interesting type of meaning is that built from within the piece', he says. 'This

is something that plays a role in all good music. It's a question of how musical statements

are placed in relation to one another, so that a language is created within the piece. On the

other hand, there's also meaning that stems from outside the music. Romantic music is

full of this – Mahler too –, where a gesture derives its specific colour by referring to

something else. But in this regard, I think, I'm more classically oriented; generally

speaking, I want to make things that work absolutely free of external connotations. And

sometimes, I carry this idea very far, if only to prove that the material itself is totally

unimportant. It doesn't matter what you use; it's how you use it that counts.

'That's what's so great about Webern for example. Everything simply is something,

each note an event. That quality gets lost in most serial music, it crumbles away so to

speak. So many pieces from the fifties and sixties did essentially nothing more than

generate material. By way of illustration: it's my experience that in any random telephone

number some kind of idea, structure or symmetry can be discovered. And that's precisely

where the danger lies. It's what happens in a lot of serial music. One way or another, the

listener will always discover something in it. So this type of music gets its meaning by

grace of the listener's creativity. It's often very tiresome. You wish the material had

something to say.

'That's why I sometimes use things that normally speaking are absolutely void of

meaning but take on an almost mythological significance when used in a certain way.

Like the page-turning in the kettledrum solo. I want a kind of music that maintains a

continuous balance between dream and reality. The dream as a temptress, who seduces

the listener, and then suddenly is interrupted by "daily life", represented, for instance, by

the turning of a page, which totally alters your perception. The nice thing is, if it happens

often enough, the page turn becomes an aesthetic object. It becomes a part of the dream,

and you enter a new world.'

Om mij mijzelf met mijn aan mezelf en mezelf en mijn eigen is so totally geared towards

the listener's physical presence that even a video filming of it would fail to convey the

experience. For instance, there is a long passage where the hall is cast in absolute

darkness ('the "Night"', says Van de Putte) and out of it, indefinable sounds and

tantalizing silences reach out to the audience, who by now is straining its ears to the limit.

The question arises: to what degree is such music still music?

'To me it is music, but, in my opinion, the whole question has no relevance', parries

Van de Putte. 'I think that this is my whole concept of life – that you can't separate things

from one another. In composing the kettledrum solo I began simply with the notes, but at

a certain point those ideas started creeping in. And I let them, too, because when that

happens I feel the piece will really turn out well – become something that is very much

me.

'I lived for a time in a house that was crawling with beetles. At night it was horrible.

After turning out the lights I'd lay there waiting to hear something. After a while I'd get

so tensed up that I couldn't be certain whether I'd heard anything or not. That experience

found its way into the "Night". I find that really exciting, that at one moment something

may seem totally insignificant and the next it suddenly swells to monstrous proportions.'

He points to a pile of small bells on a table. 'Those bells, they're a perfect example. They

lay on the ground and now and then the kettledrum player steps lightly on them... and

whenever he does, he sets time still. Then comes another fermata, he waits – scratches a

bit on the drum head. It's nearly a melody. I could almost sing it. You have to feel it as

one, long line, despite the length of the fermatas. And all of a sudden, as if by inspiration,

he gives a violent kick to those bells, fortississimo. An unexpected possibility of that

material.'

He turns the conversation to Thomas Bernhard, one of his favourite writers, whose texts were the

beginning point of Es schweigt and In hora mortis. 'Bernhard unravels the small things of

life. Actually, he's a very romantic author, although he doesn't write about heroes or good and evil. No,

in his work you'll hear more about itching, and all those other things that life is full of but nobody

really talks about. There are sentenccs in his work that get completely caught in their own words. For me,

there's a link with musical language in this: the idea of a tremendous amount of motion, that something is

always changing, but that, ultimately, everything stays put. I see a lot of this in my own work, too. But

if you want to have something conveying boredom, for example, something that lasts too long (too short or

too long, that's what intrigues me) it's not particularly productive to do it in a boring way. It still

has to maintain interest. I think it's very important that a piece of music takes hold of the listener,

that when it's finished the listener feels that he's been transported somewhere.'

Van de Putte is booked full for the coming years. The Asko Ensemble and Orkest De Volharding have both asked

that he write a piece for them. Two large-scale works are in the planning, in sequel to the kettledrum solo:

Un, for three recorders and piano, which will be premiered in December in Zaal de Unie in Rotterdam,

and Quelli che restano for the Novecento ensemble. He is currently occupied with a solo for the

soprano Ingrid Kapelle – 'I am her mouth' – which will be performed in the first week of

November, again in De Unie, as part of the ConSequenze festival. 'This is one of my "too much" pieces

I've heen trying to mount for years. Things fall into two categories', he explains. '"Too little", which is

waiting for things, and "too much"; euphoria, when you feel wonderful, associations connecting in a flash,

like what happens in a good conversation. That's one of life's most beautiful emotions. The soprano solo

focuses very much on exaggeration: a woman stumbling over her words, trying to say so much all at once that

she gets nowhere. The text is based on Dostoyevsky's Notes from the Underground, one of my favourite

books.'

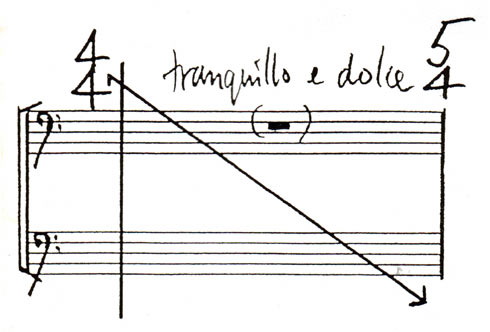

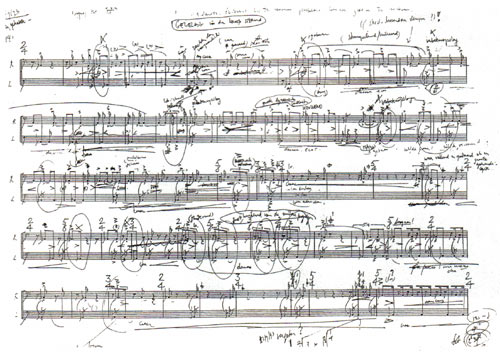

He goes to his study and returns with a sketch. 'Actually, up to now I've only worked out the rhythm', he

says. 'This is where she begins counting. It's like a nervous tic, she just can't stop. Everyone knows that

type of thing, I think, those strange ways we have of killing anxieties. It goes incredibly fast. It begins

with one, two and continues up to twenty, and then she gets lost in counting.' He reads

– with growing excitement – from the text: 'Six thousand – thousands of – hundred

thousands! – very expensive – I like that, suddenly the numbers take on a thoroughly different

meaning – everything, every one, everywhere, more, much more.'

It seems a far cry from Dostoyevsky, but for Van de Putte it's all the same thing: 'Look, the interesting

part obviously isn't merely taking same text and putting notes under it, but rather in making the essence of

the text perceptible in a musical way.' He picks up a book. 'Dostoyevsky keeps talking about 2x2: "

2x2=4, that's a formula, And 2x2=4 is no longer life, but the beginning of death."

Numbers are often used in this way. We need them in order to deal with the chaos around us. But that chaos

is life. That's what Dostoyevsky says, too: "I agree that 2x2=4 is an excellent thing; but if we're going

to start praising everything, then 2x2=5 is sometimes also a most charming little thing." What I try to

do is to use the numbers in a emphatically emotional way. Not as formative elements, but nearly as if they

were living organisms. So that they become almost poisonous. The constant exaggeration throughout this

piece, the woman's personality type closely resembles the man's personality in Dostoyevsky's book. It goes

so far that at a certain point the soprano refers to herself as being male. This mixes even more factors. The

curious thing is: from a realistic standpoint, it deals with untruths, but seen from an artistic standpoint,

and from life itself, it's closer to truth.'

'12/18/92. Drum head as cheek. The anguished one (= man) attempts reconciliation, The beaten one

(= kettledrum) caressed.'

As programme notes for Om mij mijzelf met mijn aan mezelf en mezelf en mijn eigen, Van de Putte

collected a number of sketches offering glimpses into how a detailed score emerged from indecipherable clumps

of notes and comments like 'Big beating heart' and 'falling and getting up once more like a grand invalid'.

'I always compose real-time,' he explains, 'which is to say that I always measure time. I sit at my desk

and imagine it. Same passages, I'll have to redo ten times before I know, from the feeling in my head, that

they're right. These things can't be taught, they just have to be felt. And my music has very much to do

with experience.

'It usually starts with my having same idea, often just a little thing or a few notes. I have to be

convinced that the idea is a good one, though. And if it is, I can usually visualize the entire piece that

is, the form and the type of things that have to happen in it. In the process of writing, everything gets

worked out in greater detail, of course.

'The kettledrum solo was a first attempt at doing something with rhythm that was more than just variations

on a continuous pulse – what you often find in percussion pieces, they're so quantitatively conceived.

For the kettledrum solo, I began with one of the most qualitative rhythms:  . It's a

romantic rhythm, you know, something very nineteenth-century, from Bruckner or Wagner. It's a very limited

element, too, but with something euphoric or possessed about it. And that's what I want: a rhythm with a

will of its own. It has a pulse, but one that keeps changing it's mind, so to speak: constantly moving

forward, but always in a different way. Still, there's a thread running through it.'

. It's a

romantic rhythm, you know, something very nineteenth-century, from Bruckner or Wagner. It's a very limited

element, too, but with something euphoric or possessed about it. And that's what I want: a rhythm with a

will of its own. It has a pulse, but one that keeps changing it's mind, so to speak: constantly moving

forward, but always in a different way. Still, there's a thread running through it.'

In april of this year Peter Adriaansz performed Van de Putte's latest composition, Terra, on the

organ of Rotterdam's St Laurens Cathedral. One more work that is but a part of a larger whole and once again

with the composer exploring beyond the customary way of using the instrument. A curious discourse filled with

wavering tones and moaning chromatic seufzers gradually makes way for a barren landscape –

little ringing bells and cowbell clanging paired with loud scraping and stamping, up above in the organ.

'That's the Van de Putte touch', concluded my neighbour, a well-known critic, during the intermission. 'You

get spanked every time.'

Van de Putte explains that he planned to use the church bell – invariably, a source of unasked for

counterpoints at organ concerts – in the composition. 'The climax of the piece coincides with the church

bell striking the hour; it has to be timed to come at exactly nine o'clock. And when it's there you hear all

kinds of shifting pulses: the most obvious, of course, being the church bell itself. I wanted to combine this

with a sound like something immense walking by, with thundering steps. It's part of a progression in the

sound that begins earlier with scratching on sandpaper, changes to stamping, and then to hammer blows on a

piece of wood.

'I have to admit, I make it hard for myself, but that's the way it is. The church bell, the page-turning,

it is something. It's much more than just sound. There is an entire complex of meanings connected to

it. And it's very primary, everyone recognizes it, you don't need to look it up in an encyclopedia. That's

why they can be infused with meanings that are below the surface, that nobody can put a name to but

everybody can feel. And this is precisely what I want to do with my music.'

(transl.: John Lydon)

© Frits van der Waa 2007