This article was

published in

Key Notes XXVIII, 3, september

1994

and

in a shorter Dutch version in

Entr'acte of July

1994.

There's also a German version.

Guus Janssen and the

skating-on-thin-ice

feeling

Guus Janssen (1951), composer and improviser, is always on the

lookout for material

that is suitable for carving-up. Music should never be put in an

straitjacket, but

then, that is, a question of trompe l'oeil, or rather tromper

l'oreille. How do

you make a hi-hat drunk? Answer: you equip an entire studio.

Composer Guus Janssen and I live in the same village. It is

called Nieuwmarktbuurt

and lies amid the many others that together form Amsterdam.

Walking through the

Buitenbantammerstraat to the Prins Hendrikkade, I think of the

first time I heard

Guus's music. It must have been in November of 1980, when the

Netherlands Radio Chamber

Orchestra performed his Toonen at Vredenburg Music Centre

in Utrecht. Or was it

before that? Toonen had been performed a month earlier in

Donaueschingen, and I

seem to remember something about a radio broadcast, with the

audience buzzing in

indignation.

The music of Guus Janssen was - and still is - wayward. Very

Dutch too, like the

bicycles here: rickety and rattling perhaps, but more economical

and manoeuvrable than

any other means of transportation. It is possible that people

outside Holland do not

always see its charms. But I am devoted to Guus's music, in

roughly the same way I am

devoted to my bicycle.

I have seen him improvising at the BIM-house, also nearby, but in

the next village, across

the water of the Oude Schans. Raging, bone-dry martellato's, as

though he were

trying to hammer his fingers through the keyboard. I heard him

play the harpsichord in

The IJsbreker. Pogo III, the piece was called, teeming

with tones hopping about

like so many trained fleas. I ran into him in the Amsterdam

Concertgebouw when Riccardo

Chailly conducted Keer. ‘What that man does... that

the piece sparkles

everywhere’,

said Guus. ‘It's as though he gave it a good buffing with

Lemon Pledge.’

His face sparkled

too.

There is a splendid view of the IJ from where Guus lives. His

home, though not so bare as

it was ten years ago, is still soberly furnished. I dropped by on

several occasions. The

first time was in 1984, just after he won the Matthijs Vermeulen

Prize (Amsterdam's annual

music reward) for his composition Temet: completing the

recognition of his dual

musical career, for he had been awarded the Boy Edgar Prize for

Jazz and Improvised Music

three years before this.

As soon as I come in he begins telling me about the piece he is

working on: a rush assignment

for the final concert of Gidon Kremer's Carte Blanche Series in

the Concertgebouw. It is for

a small ensemble in which, next to the violin, a high-hat is

prominently featured. ‘It

will probably fall outside of all accepted and even non-accepted

norms’, says Guus.

‘I took the assignment on condition that I could base the

work on some existent material

of mine. To write it from scratch would have been impossible in

the month they're giving me.

I've taken a theme from Hi-hat: it's also on my solo CD. I

imitated the hi-hat on the

piano in that piece. On the CD I improvised an elaboration of the

theme, but I could just as

well compose it. It's to be a kind of essay on jazz: swing, in

this case. About a swinging

violin, and a swinging violin quickly sounds wrong to my

ear.’

‘Whenever I think of the violin in a jazz context, I

remember a character from one of

Pasolini's films, I don't recall which. A man called Herdhitze, a

blue-blooded type, who lives

somewhere on an estate in Germany. He expounds incredibly

frightening theories. Speaks German

with an Italian accent and, to top it off, preferably while

playing a harp. I can't forget that

image, or the name. I want to recreate the same feeling in this

piece. The name really fits

too, it has something so sharp about it. Kremer is looking for a

lighter segment in his

programme - he said a homage to Stephane Grappelli, but at the

same time he sounded ambiguous

about it. I'll give him the lightness, but then with a

Herdhitzian undertone, which may turn out

to be extremely macabre.’

In what way does it fall outside of all acceptable

norms?

‘The hi-hat: first I'll poke around with it, almost

literally. Eventually, it will start

playing that same basic pattern it always does in jazz, but

endlessly varied and elaborated on.

One could ask if this isn't going too far: the hi-hat pattern is

jazz, no bones about it. A

different composer would leave it aside. But it's another one of

those trivial interests of

mine. I can't defend it, I just do it. And then hope it turns out

to be a good piece.’

A state of marvelling, in no way clashing with his

levelheadedness, is a natural condition in

Guus's personality. He seeks out and gives form to the logic of

amazement in his music. This

is often confusing, and at times even extraordinarily comic.

Preludium, the first improvisation on his harpsichord CD,

opens like a piece by

Scarlatti, but, shifting gears abruptly, it thoroughly derails,

and before you know it, it lands

in a distorted blues pattern. Anything can happen, but the

disarray is never without its own

order. His improvisations are veritable instant-compositions,

hence he is not a jazz musician.

He always puts jazz between quotation marks.

‘I look for material that's suitable for carving-up’,

he says. ‘And that's not

Wagner, at least not for me. It's not that I don't find his music

beautiful, it's incredibly

beautiful, but even today almost everyone is preoccupied with it.

A lot of times I have the

feeling that we're still living in a sort of convulsions of the

Romantic Era, at least in

composed classical music. Really abendländisch - the

field has been literally

exhausted. I feel exhaustion creeping over me whenever I consider

adding something to

it.’

‘Jazz, to me, is a kind of musical reality - one of the many

in fact - and this reality can

be taken as a starting point in creating something. It can be

confronted with a separate reality,

or elements of the one can be transplanted to the other, and so

on. Many composers consciously

close themselves to these types of realities. They keep trying to

follow a single path, and

that's enough. Not that I don't try to do this too, but it's very

nice to look around me along

the way.'

‘I recognize there are many different paths, each with its

own charm. You're free to choose

a prickly mountain trail, but you could also take a pleasant

beach boulevard. And on top of it,

all these different paths influence each other too. This range of

possibilities really appeals

to me. Don't forget, in life too, if all goes well, you come

across the most widely divergent

things. I once read in an interview with Edo de Waart that he has

model trains. That's

intriguing. He conducts a symphony by Mahler, or an entire opera

by Wagner, and then goes home

and plays with a model train. In composing, similar things are

possible. It's not so easy in

performing, but a composer can integrate the two worlds, so to

speak. Of course, the crucial

issue is in how far the artistic personality remains

intact.’

‘Another example that comes to mind is Philip Guston, the

American painter friend of Morton

Feldman. For years he worked at monochrome surfaces and very

abstract things. But when he came

home from his studio he would sit at the kitchen table sketching,

let's say, an ashtray. The

incongruity of the situation nagged at him more and more. There

was something wrong with it: he

got every bit as much pleasure from drawing the ashtray but he

had no desire to give up his

studio. Then he thought: “I'll just make a painting of the

ashtray.” That was at the

end of his career. In the portrait of Feldman on his collected

essays, made by Guston, you can

see the same dilemma: it's unheard of, an abstract painter

drawing a head like that with a

cigarette dangling from the lips. I think it's wonderful. But it

would be better not to wait

an entire lifetime, seventy years, before saying: “I think

I'll go ahead and allow myself

to use a triad in my music again”’

It must have been in 1965 that Guus's piano teacher, Piet Groot,

let him hear a Donemus LP of

Peter Schat's Concerto da camera. Guus, fourteen years

old, knew immediately: That's

what I'm going to do one day.

‘That composing began in the shadow of my piano studies.

There was not a thought in my

mind of becoming a Tchaikovsky or something like that.’ He

consciously chose to study

composition with Ton de Leeuw, even though his interest lay more

along the lines of people like

Schat and Louis Andriessen: ‘It's very risky to take lessons

from someone you already

imitate. It's no good for your development.’

‘Even before that time, I was interested in doing things

with the psychology of music

making: what happens when you botch a passage, or you're nervous.

Ton de Leeuw was against it.

He said it was too anecdotal. That's a stock objection that has

dogged me for a very long time

and I still don't understand it.’

I have an inkling of what they mean. In Toonen for

example, you let the main theme

return as though it were on a pick-up at 33 rpm, then later at 78

rpm, and it sounds in the end

as if the needle gets stuck in the groove. There's some story

behind it, and it does in fact

add an extra-musical dimension.

‘True’, admits Guus. ‘But you could go on to ask

if there's anything wrong with

that. That type of aural information didn't exist before the

pick-up. So it's impossible that

anyone could have got the idea of using it. But historically,

there certainly have been

composers who used the things they heard around them. The clatter

of horses' hooves for

instance has often found its way into music. But you don't hear

it in the streets anymore, so

it's no longer used. It's all a matter of how you handle such

things.’

It is tempting to compare Guus's way of speaking to his music:

one moment faltering,

circumspect, hesitant, and then fluent, teeming with asides and

unfinished sentences. But in his

music, these qualities are premeditated.

‘Most times I come up with the material sooner than the

form. In any case, I'm not a

composer to choose a form and then fill it in. Usually, it works

both ways: a composition grows,

like an organism. If one arm grows, so must the other, and that's

a very complicated business in

composing. The context changes with each new alteration, so it

can lead to endless rewriting, or

to cutting and pasting.’

‘I love a kind of folly. But good folly has to be done well,

it can't be corny. in Keer

I wanted to construct a texture that keeps dissolving, but each

dissolution poses at the same

time the following question. I imagined waves dashing on the

shore, washing over each other.

The question was: what material would fit the image? And then:

what tools were need to shape the

material? In a manner of speaking, I had to equip an entire

studio before getting started.’

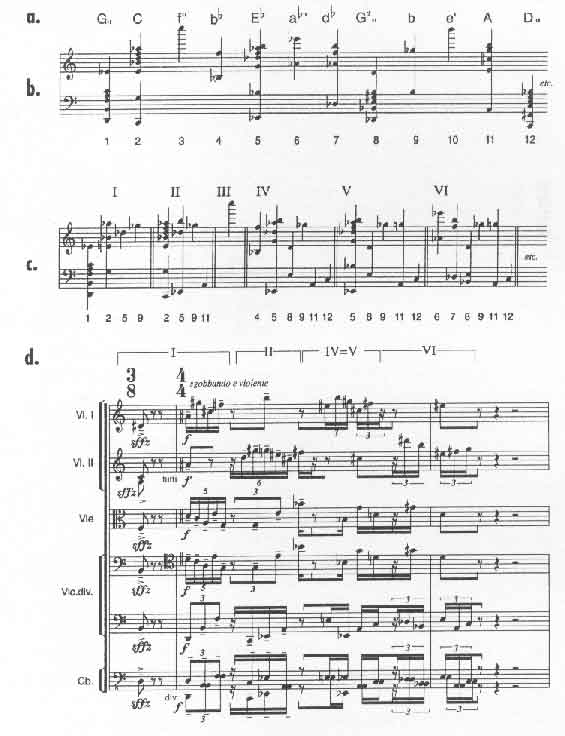

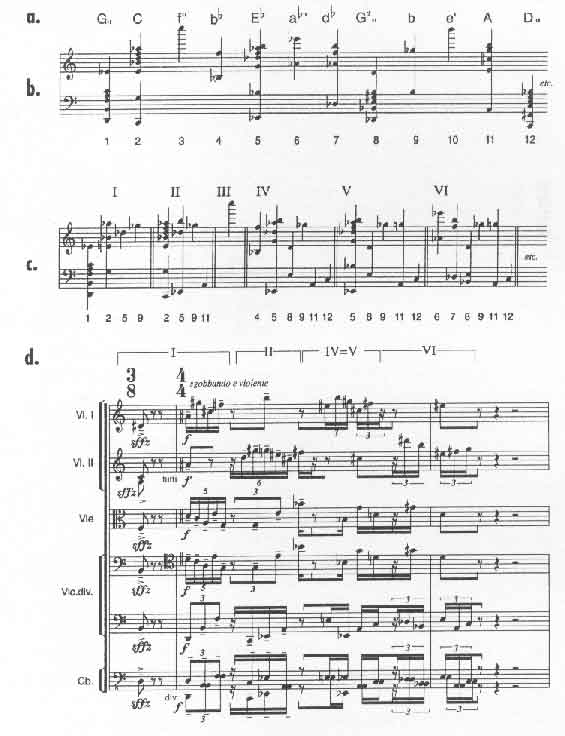

Now sheets of music line the table. Schemes with chords and

rhythms. Guus relates that in earlier

compositions he often employed a type of ‘endless modulation

principle’ through the circle

of fifths. He began with a few tones from the scale of C that

would immediately modulate to G,

then D, and so on. The quicker he swirled through the circle of

fifths, the less ‘tonal’

the music sounded. But through constant alterations in the rate

of modulation, the music would

evoke tonal associations, without actually being so.

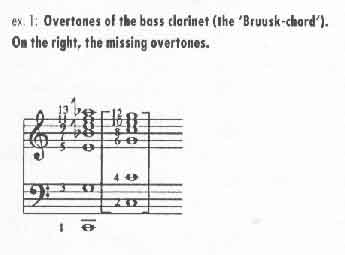

Other compositions, namely Bruusk, were based on the

overtone series of the bass clarinet

(ex. 1). Concealed in this series, made up of the uneven

harmonies, are, moreover, two dominant

seventh chords. In Keer, he combined the two principles by

applying the endless modulation

principle to the Bruusk chord. ‘I had to resort to all kinds

of tricks to close that immense

hole at the base, it's gaping’

Guus let the 'root' of each following chord leap one or more

octaves (a), omitted in many cases the

lowest tone of the chord - as well as the very highest 'peaks'

(b) -, and expanded each chord to a

twelve-voice texture by foreshadowing the following chord

(c). The result was an extended cycle of

'tone reservoirs', that enabled him to build the

'string-instrument clouds' he envisioned

(d).

‘I very much like the idea of combining that

tenet of twelve-tone technique (that all twelve

tones be sounded before moving on) with something so simple and

natural as the overtone series',

he said in a lecture about his music. ‘It results in the

trompe l'oeil of a music

that is boundless and directionless but at the same time seeks

out directions in a mad way

(unrationalized and machine-like). Is there harmonic progression

in the music or not? In

Keer the pitch machine also runs at repeatedly changed

rates. When it looks as though it

will come to a stop, we hear endless chains of arpeggiated

dominant-seventh chords.'

In this way, Guus consistently probes the margin between the

familiar and the unheard of.

‘The only way I've ever been able to listen to strict serial

music is by recognizing things

in it: Ah... I hear a fifth, or a triad, or even a children's

song. We are evidently

conditioned this way. That's what comes from a lifetime of

musical education. Maybe there are

people who can shut it off. That would be ideal, of course, at

least for this music. Then it

would be appreciated on its own terms, so to speak.’

Yet, you often work with rows, I counter. Is that an

influence of serial thought?

‘In a sense, I began with serialism. I made actual

twelve-tone compositions when I was

fourteen, in my own primitive way, of course. And now... I

certainly turn to rows for more than

just working out the pitches, for rhythmic things too a lot of

the time, although you can hardly

hear it in the music. It often comes up when I'm trying to

construct a continuum, something that

moves but doesn't develop. If approached intuitively - to my

mind, the better way - then it's

off to a good start, but things creep in unnoticed. After a few

bars it might turn out to be

much too fast, proportionately, to the beginning. So then there

would be development. If you're

clever about using rows, you can avoid problems like

this.’

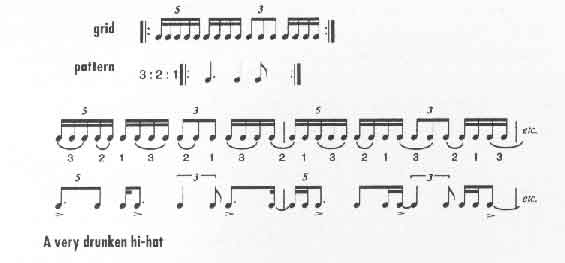

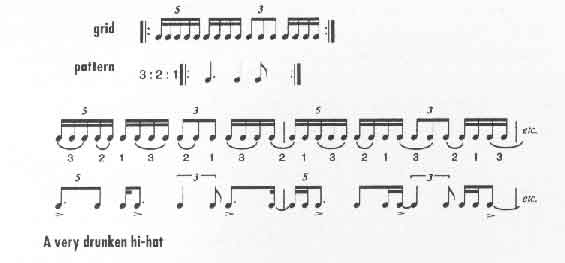

‘The hi-hat pattern, say, could be written in such a

way that it begins to waver. I

could get this effect by running it through a grid that has a

variable pulse in itself.’

Guus takes a piece of paper and begins to write: quintuplet,

quadruplet, triplet, quadruplet.

‘This isn't what is played, it's the grid that the hi-hat

pattern is pushed through. 3:2:1,

very simple actually. Essentially, a form of isorhythmic thought,

I'd say.’

‘Now, if we play this...’, but then the

craftsman takes over: ‘No... this doesn't

really work, does it. Well, if we were to do something with the

accents, you could hear it a bit,

it would sound like a very drunken hi-hat’

Guus based a number of compositions on this principle, among

which are Voetnoot (see

example) for

piccolo, and the orchestral piece Deviaties.

‘Deviaties is totally based on a

2:1 ratio, the swinging rhythm, in fact. This caught my

imagination for the simple reason that

swinging is such a strange phenomenon, it can't be pinned down. I

worked it out in repeatedly

changing proportions, 3:2, 5:3, and so on. It has a strong

stammering effect. But I also coupled

it to various tempos in Deviaties, giving, so to speak,

one bar a particular rhythmic

feel, while the next could suddenly be fast, but with the same

stammering effect. I was pleased

with how it turned out. A real combination of things you can't

combine: rickety but at the same

time performed with unswerving consistency. This type of thing

can't be done in

improvisation.’

‘I'm sure it stems from my dissatisfaction with rhythms that

sound like they're being

counted. In so much music I get the feeling: oh, this a

triplet, or, this is a quintuplet,

as the case may be. Even in my own pieces. I don't get that

feeling with improvised music. It's

the same type of thing with good Baroque music. You don't hear a

single sixteenth-note, and in

fact it's nothing but. This naturalness of rhythmic flow

intrigues me and that's why I do this

type of things. It's absolutely impossible to hear any given

metre or even an accented beat in

Deviaties. Even though everything has been carefully

measured out, it sounds haphazard.’

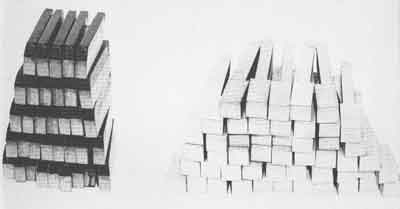

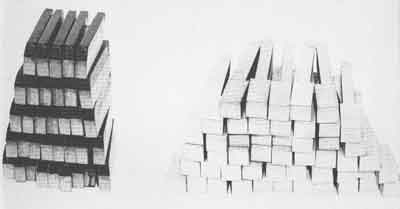

At home, rummaging through my LPs (yes, I do still play them), I

come across Guus's LP of

improvisations Tast toe. I am struck by the same

shortcircuit when I see the cover.

A black and a white pile of rectangular sticks... #shortcircuit#

- no... piano keys. Disassembled

and then reconstructed in an new way: the perfect metaphor for

Guus's music.

Another LP, Guus Janssen on the line,

hand-dated April 24, 1980. Apparently, I had come

into contact with Guus's music earlier than I had thought. Now I

remember having had the score

of Brake in my hands, even before the LP. (Looking over

Guus's liner notes I read:

‘Someone who makes mistakes while playing will try to regain

control by slowing down (the

rallentando), which is also what happens in this piece.’)

The notes looked so strange on

paper, I could make neither head nor tail of them.

‘They didn't understand it at all’, says Guus. He is

speaking of Juist daarom,

written in 1981 for Ensemble M. ‘Well, it is in fact a very

strange piece, a dear but

peculiar child. But it's the first of a line of compositions,

Streepjes and Temet,

for example.‘ Giving the impulse to set out on this line was

an encounter with Six

melodies, an early work of John Cage for violin and piano

composed in 1950. ‘I

performed it myself, with Jan Erik van Regteren Altena, and it's

never really let go of the

composer in me. It has such a measured and businesslike quality,

and a paper-thin lyricism,

a real skating-on-thin-ice-feeling.’

All the reason for Guus to programme Cage's piece in a

‘composer's portrait’ in this

years's Holland Festival as a tangent of Guus's opera

Noach. Next to his own music, a

trio by Wolfgang Rihm will also be performed there. ‘Just a

single movement, the others

are a bit further from my taste, you might say he expands on

Schumann. But the first movement

is very concentrated and very sharp. It's also about very

primitive musical premises: fifths,

unisons, all those basic concepts one finds at the beginning of

music theory books. I'm really

taken by it and this fellow Rihm is a first-rate composer;

especially that breadth of view,

something that I perhaps lack.'

I don't quite understand what you mean by breadth of

view.

He laughs a bit. ‘How can I put it?... What I do is a sort

of burrowing, that's how it

feels a bit. And burrowing is burrowing, although it can be done

in an very thorough and

interesting way. But with Rihm, there's more of that Caspar David

Friedrich feeling (a German

Romantic painter) and inside that panoramic vision the small

human being goes almost

unnoticed.’

‘This, too, is not what I want to do. Well, I sometimes do

take a stab at it. There's a

passage in Noach, for example, describing the sphere of

paradise on the island of

Mauritius when the dodo still lived there undisturbed. One of

these motionless passages. That's

my stake when it comes to that breadth-of-vision quality. It's

easier in opera. It comes of

itself, if for no other reason than that the time is structured.

If I were to burrow away

throughout the entire two hours of the piece, I think it would be

extremely tiring for the

audience. So I immediately set out to find ways of creating this

tranquil effect. And, obviously,

the most beautiful, or starkest contrast to burrowing is doing

nothing at all. Call it

structured standstill.’

‘It has to do, of course, with the sorts of communication

between Mr. and Mrs. Noah. There

just aren't any! All shapes and sizes of non-communication, and

the most basic form is to

totally ignore each other - what normal people do with strangers

when they pass them on the

street.’

Guus Janssen, the note-burrower, master of the finely etched

line, finished an evening-filling

canvas last year: Noach. Clearly, it is not your everyday

opera, for Guus is Guus. And its

librettist, Friso Haverkamp, who had teamed up with the composer

in a previous opera, Faust's

Licht, is not your everyday writer either.

Noach is a topsy-turvy, cynically framed rendition of the

Old Testament story. The dove

becomes a Skeleton Bird, the rainbow is transformed into a

high-voltage arc of light. Noah is

portrayed as a self-appointed god, glorying in the annihilation

of animal species. He becomes

embroiled in an head-on conflict with his wife, who sides with

the animals and, perched on the

back of a humpback whale, a ‘counter-ark’, refuses to

come aboard.

Guus: ‘The story deals on one level with man's abuse of

nature. Noah, for example, has a

sort of species-meter, a device for gauging the rate of

extinction. In actual fact, it seems

that every fifteen minutes an animal species dies out somewhere

in the world. This contraption

of Noah's measures in actual time, demonstrating over the course

of the opera that at least eight

sorts of animals have vanished forever. In the two years that I

was working on the opera these

types of things would come up all the time. I'd be sitting with

the newspaper in the morning and

read an item about some sea captain pumping oil into the ocean,

pictures of birds washed up on

the shore. You can imagine him standing there on the bridge: he

simply becomes Noah. It fires you

up to get down to composing.’

‘It's a real opera, though, about emotions, expressions of

feeling... but not in the sense

you find so much in classical operas: am I in love or am I

not? Noah's raving lunacy

stands at one end of the spectrum, and Mrs. Noah, with her

profound sorrow and rage, is at the

other end. That was something very new to me, I had to dig into

very different reserves. It was

beautiful at the concert performance of Wening, the fourth

act, that people were really

moved - which is also very operatic, in a Verdian sense.’

Noach is scored for an enlarged setting of Guus's own

ensemble, which appears in the

production under the name of New Artis Orchestra - with the

permission of Artis, Amsterdam's

zoo. Guus describes the final product, a score of 400 pages, as

being ‘as full of holes as

a Swiss cheese’. Alongside the through-composed sections,

namely, are segments for

improvisation, guided by various sets of rules. In addition,

there is a battery of electronic

apparatus: a vast array of taped (mostly animal) sounds, ring

modulators, etcetera.

‘Really old-fashioned stuff’, says Guus, ‘but for

what I needed, these

Sixties-tools work the best.’

‘The music was made in the same way as the pieces I write

for my ensemble. The composed

parts are even rather simple. All those things I'm up against in

composed music have no part in

improvisation. On the contrary, that over-tight rhythmic quality

you find in a lot of composed

music comes to good effect here. It can be a catalyst for all

kinds of escapades.’

The catch to this overall conception is that the opera can only

be performed by the musicians

for whom it was written. The participation of the Tuva Ensemble,

a company of Siberian

overtone-singers, makes it unlikely that it will be produced

again after its series of

performances in June comes to an end [* I was wrong here].

‘The Tuvans sing the fluting of the wind, that was the first

association that came to my

mind and that's the reason I asked them. Wind plays an essential

role in the opera. But, they

also sing the “wind” in the sense of

“anima” or “spiritus”,

the soul or spirit. You can imagine all those extinct animals

hovering over the stage in the

form of wind.’

‘Not so long ago, I heard Stravinsky's The Flood, and

there's a moment in it too

where Noah's wife hesitates. It's just a brief moment, strange

enough, and ten seconds later

she's persuaded. In my piece it lasts two hours an even then she

won't come aboard. She

understands that it's all Noah's delusion and she takes the side

of nature and the free

animals.’

Little solace is to be found in the close of the opera.

Everything comes crashing down. But

the story could start again where it left off. Guus: ‘It

closes with the line it began

with. Open ended, and that's a good thing too. Just imagine if it

had turned out a moralistic

tale.’

The next time I see Guus is on the 1st of March. Gidon

Kremer has just finished

playing in the Concertgebouw and a small crowd throngs outside

his greenroom. Among them, I

see Guus Janssen and Theo Loevendie, both with a score tucked

under the arm. They both have

been granted an audience. Guus waves cheerfully.

Printed on the cover of the score is the title Klotz.

‘I looked it up’, he says.

‘It comes from Porcile. And the man who plays the

harp is Klotz, not Herdhitze.’

We leaf through the pages. ‘Look at this’, gushes Guus,

pointing at one part. ‘I'm

especially pleased with this.’

What does that mean, ‘civettuolo’, I

ask. ‘Flirtatious’, answers Guus.

‘That's now exactly what I mean.’ Then the door opens

and score in hand, he is swept

along inside.

© Frits van der Waa 2006

|